It

was an army of Vikings with the objective to avenge and conquer England.

Because of their known ruthlessness and savagery the English chroniclers

labelled them as the Great Heathen Army. But others labelled it as the Great

Danish Army for most of its warriors came from Denmark. Explore what was the Great

Heathen Army? Why was it formed and invaded England? How did it prevailed? And

how did it created an impact on history?

Formation of the Great Heathen Army

Death of Ragnar Lodbrok

Legends

said that the Great Heathen Army’s formation came as a result of the leadership

of five siblings – Ubbi, Bjorn Ironside, Halfdan, Sigurd Snake-Eye, and Ivar

the Boneless. And their intentions were revenge for the death of their father –

Ragnar Lodbrok.

Ragnar

Lodbrok, the legendary Viking leader, distinguished himself for his audacity to

attack Paris in 845. He soundly defeated the Franks in a battle and hanged hundreds

of his captive Frankish warriors. His act intimidated King Charles the Bald,

who paid him with silver and gold to spare the capital – a payment or ransom

called as danegeld.

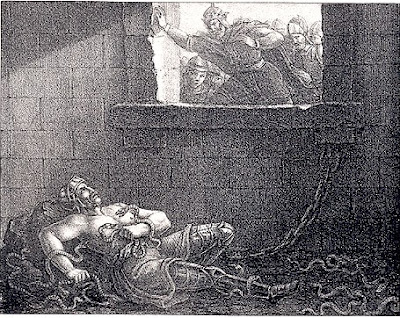

After

his Frankish adventure, he turned his eyes to another prize – England. His

raiding party, however, met stronger resistance from the English than the

Franks. Worst, he was captured by Ælla or Ella of Northumbria and sentenced to

death. He was thrown to a snake pit, but before he passed away, he uttered a

prophecy, “That the piglets will grunt when they hear how the old boar died.”

Indeed,

Ragnar’s “piglets” rampaged over their father’s death. These “piglets” were

Ragnar’s five sons – Ubbi, Bjorn Ironside, Halfdan, Sigurd Snake-eye, and

finally Ivar the Boneless. As they raged, they desire none other than vengeance

for their father.

Ivar

the Boneless, in particular, designed the invasion of England to accomplish

their quest to avenge their father. Ivar had experienced in fighting in Ireland

and earned a reputation as a great warrior and military leader. His other

brothers also shared reputations as great warriors, and together they mustered

a large Viking force like no other before for their quest of vendetta.

The Assembly

Vikings

traditionally preferred raiding tactics – meaning hit, grab and run tactics. They

disliked siege because its time consuming and they lacked the machinery necessary

to succeed. And they liked to operate into small units, usually not more than

100 men, to launch raids in Europe and the British Isles. These small raiding

parties led by a chief or an jarl or earl belonged to the same villages or clans, thus using kinship as

base for a cohesive raiding party. These parties or groupings later served as the basic unit of the Great Heathen Army

Ivar

and his brothers, however, had in their hands the prestige of their father and

their respective booties from their own raids. Not to mention, they could also promised

lands for settle for their men, for many of them wanted to leave their harsh

lives in Scandinavia. With an epic reputation and promise of wealth and land,

they convinced numerous earls and Viking parties from Norway and mostly from Denmark to

create the Great Heathen Army or what others called as the Great Danish Army.

Invasion of the Great

Heathen Army

In

865, the Great Heathen Army landed in the British Isles. Their main objective

was to capture York, the capital of the Kingdom of Northumbria, the kingdom

that defeated and killed Ragnar Lodbrok. But what was the situation of England

by 865?

Situation in England

England

had been familiar with Viking raids. After the earliest incident in Lindisfarne

in 793, more Viking raids followed, but not just limited to England, but to the

whole of Great Britain and the Ireland. Ireland succumbed to Viking invasion

and led to the establishment of Viking Kingdoms, like one in Dublin.

England,

on the other hand, fared differently than Ireland. Ireland lacked strong

political units to coordinate defenses against invasions. England, although divided

too, still managed to consolidate into different Kingdoms that offered

leadership against the Vikings. The Saxons, in particular, established the major kingdoms of Northumbria in the north,

Mercia in the center, East Anglia in the west, and Wessex in southwest. A highly organized yet still divided Saxon

England was the opponent that the Great Heathen Army had to face.

Landing

The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entered in year 865 the landing of the Great Heathen Army,

numbering from 500 to 1,000 men, in the Isle of Thanet in Kent. The leaders of

Kent feared the Viking Army and paid danegeld

in exchange for peace. Nevertheless, the Heathen Army still rampaged almost half of Kent.

In

866, the Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia and settled for the rest of

winter. They deviated from their traditional raiding and showed they aimed

conquest. They setup fortified camps from, which they based their operations.

They lived off of the land, taking horses from nearby towns and villages to

create cavalry units, while the locals submitted to their will in exchange for

peace.

Fall of Northumbria

In

867, the Great Heathen Army began their conquest by moving from East Anglia to

Northumbria, with York as their objective. The invasion went well, as they marched

into a kingdom plunged into a civil war. A conflict

between the rightful King Osbert and an outsider usurper, Ælla, the same Ælla who

threw Ragnar Lobrok to the snake pits divided the country. The internal conflict resulted to the quick advance of the Great Heathen Army to York.

However,

when the Great Heathen Army arrived in York, they faced a combined force of King

Ælla and King Osbert, who agreed to a truce to fight against a common enemy. A

battle ensued and in the end, the Heathen Army killed Osberht and according to

the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, also King Ælla. However, a legend suggested that Ivar and his brothers captured King Ælla. To avenge their father’s death,

they offered Ælla to warrior god Odin and tortured the Northumbrian King with the blood eagle.

The of Northumbria to the hands of the Great Heathen Army did not result to their retreat from the island. Rather, they continued their conquest of other Saxon Kingdoms

See also:

Bibliography:

Books:

Churchill, Winston. A History of the

English-Speaking Peoples v. 1. New York, New York: Bantam Books, 1963.

Jones, Gwyn. A History of the Vikings. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Peterson, Gary Dean. Vikings and Goths: A History of

Ancient and Medieval Sweden. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland &

Company, Inc., Publishers, 2016.

Websites:

“The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Ninth Century.” In The Avalon Project. Accessed on January 23, 2017. URL: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/medieval/ang09.asp#b36

“The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Ninth Century.” In The Avalon Project. Accessed on January 23, 2017. URL: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/medieval/ang09.asp#b36

“The Annals of Ulster.” In CELT: The Corpus

of Electronic Texts. Accessed on January 24, 2017. URL: http://www.ucc.ie/celt/online/T100001A/

No comments:

Post a Comment